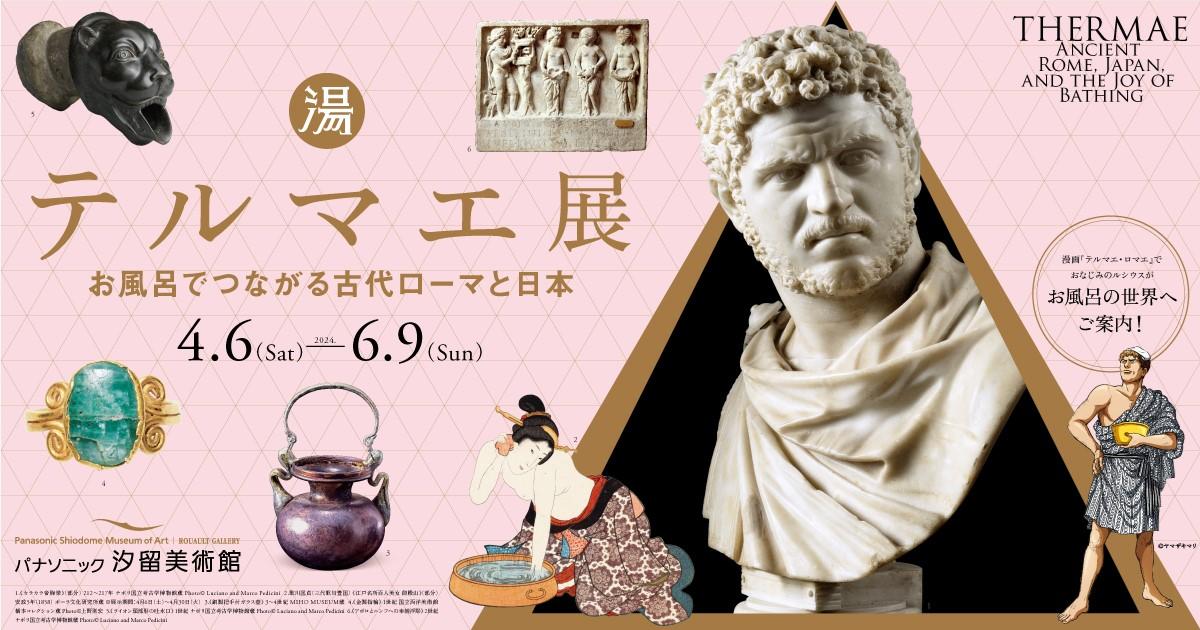

1.Includes 32 works from the collection of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, including Statue of Venus and Votive Relief of Apollo and the Nymphs!

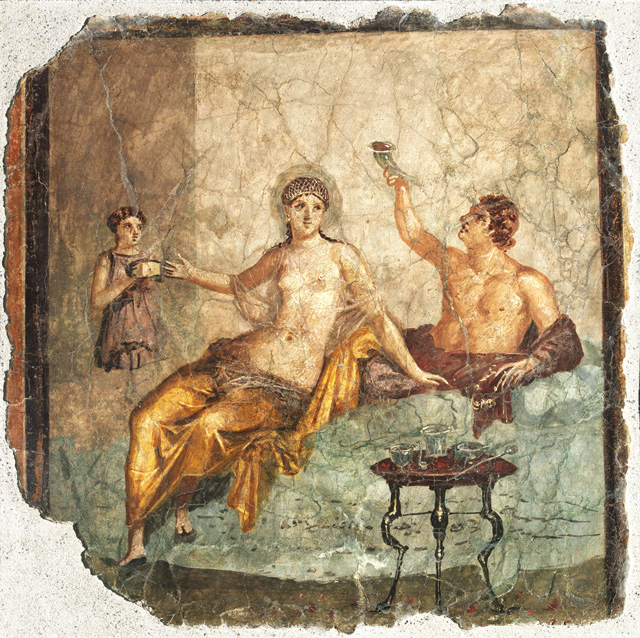

In ancient Rome, a number of large-scale thermae were built inside the city of Rome, while hot springs were also used in connection with medical treatment and fitness. Commoners lent variety to their lives by enjoying interludes at thermae after work each day and spectacles on special days. Meanwhile, the wealthy hosted lavish banquets at their homes. The exhibition includes valuable paintings, sculptures and archaeological materials that shed light on thermae and the lives of the people of ancient Rome.

2.Introduces clearly through videos and models the bathing cultures of ancient Rome and Japan!

Experience first-hand the bathing cultures of ancient Rome and Japan through a range exhibits and materials, including a speculative restoration of an ancient Roman thermae created using computer graphics and 1:250 scale model of the Baths of Caracalla.

3.Attention also given to the history and regional characteristics of Japan’s bathing culture, from onsen to sento!

Whether it be taking a bath at home, occasionally going to a sento (public bath) or visiting an onsen while traveling, bathing has become both an indispensable part of the daily routine of the Japanese people of today and a pleasure. The exhibition also introduces artworks and materials relating to bathing in Japan, providing a glimpse of a part of Japan’s history through its bathing culture.