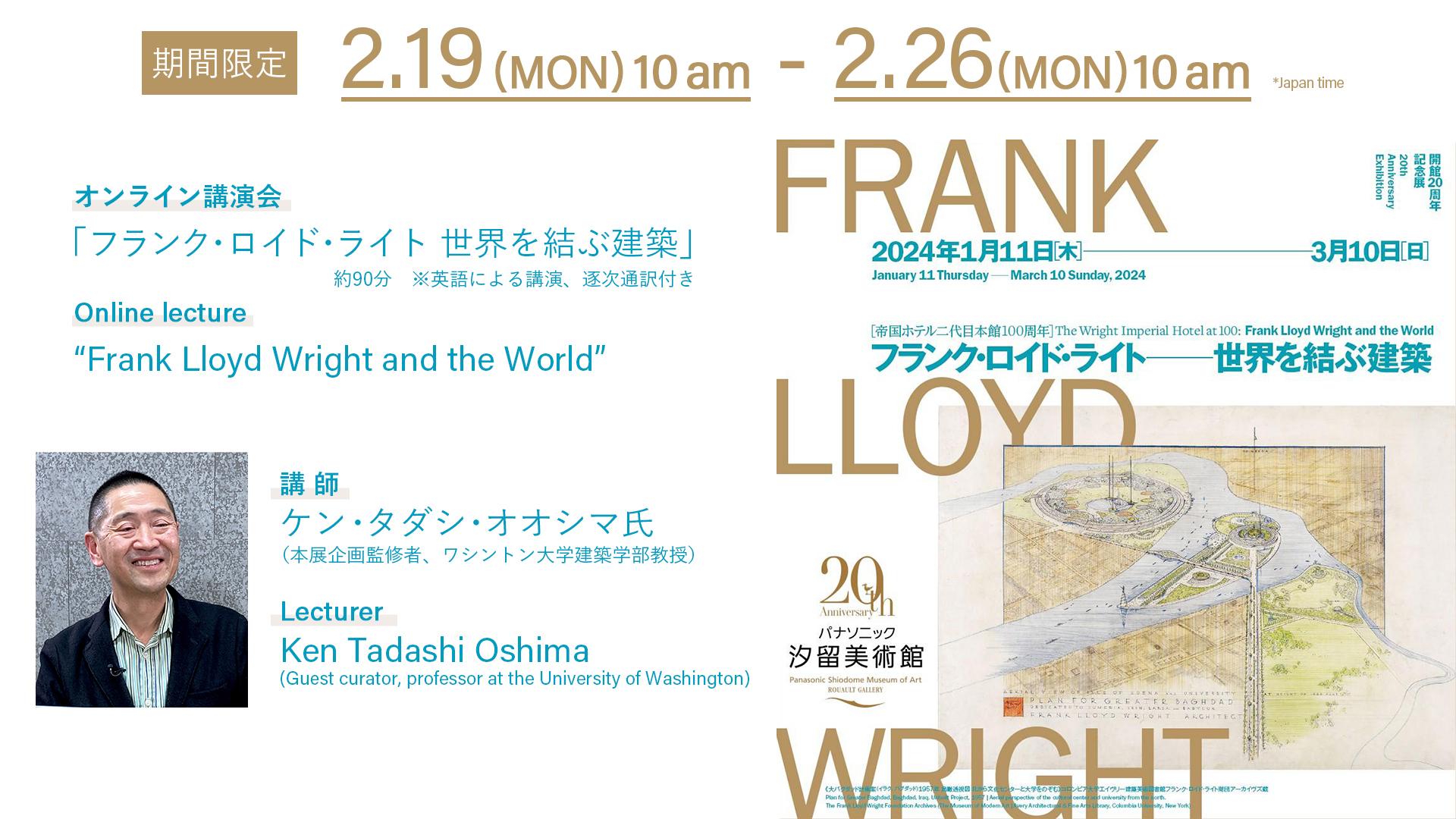

1.Intricate and elegant drawings by Frank Lloyd Wright mark their first appearance in Japan

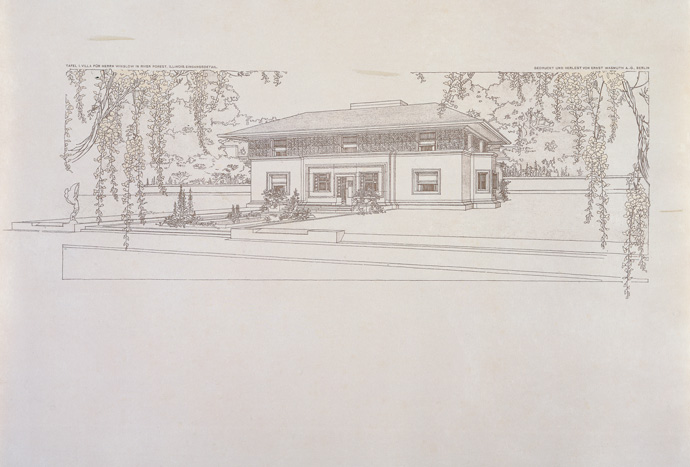

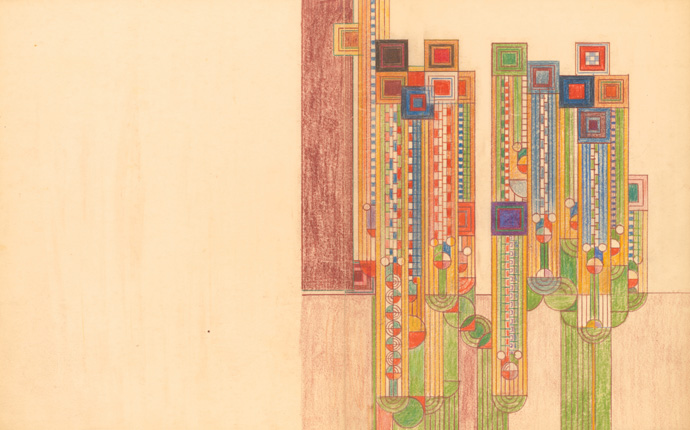

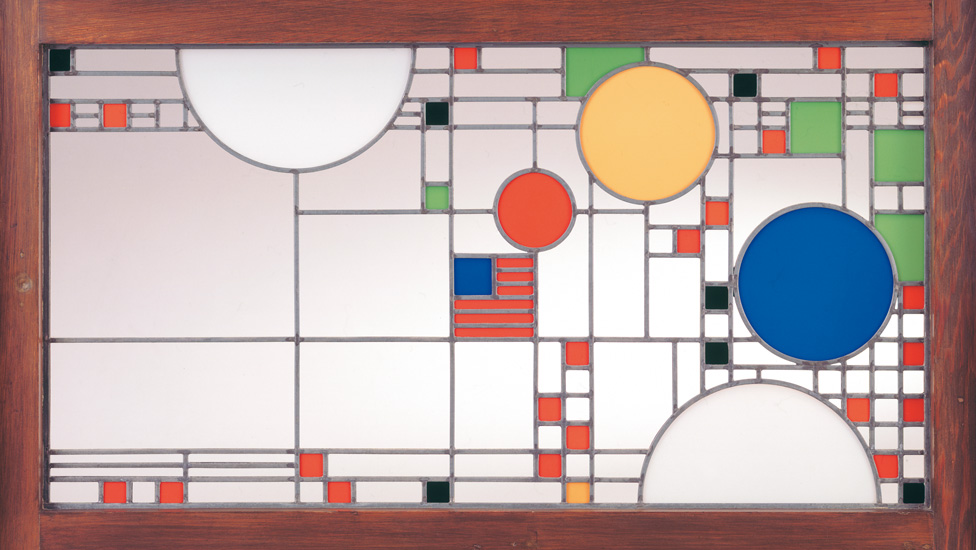

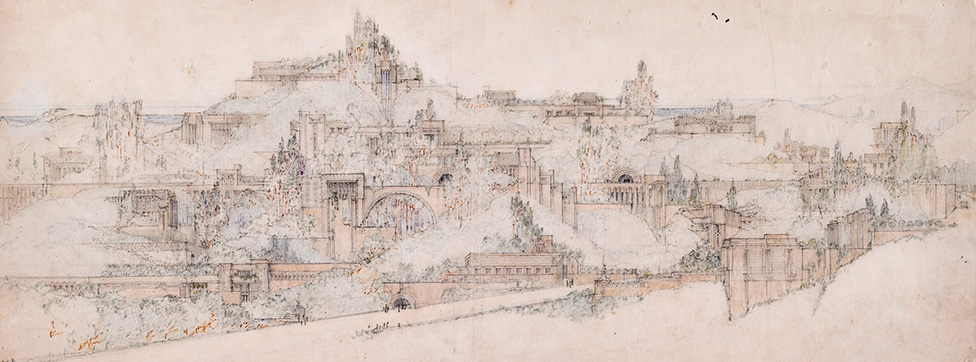

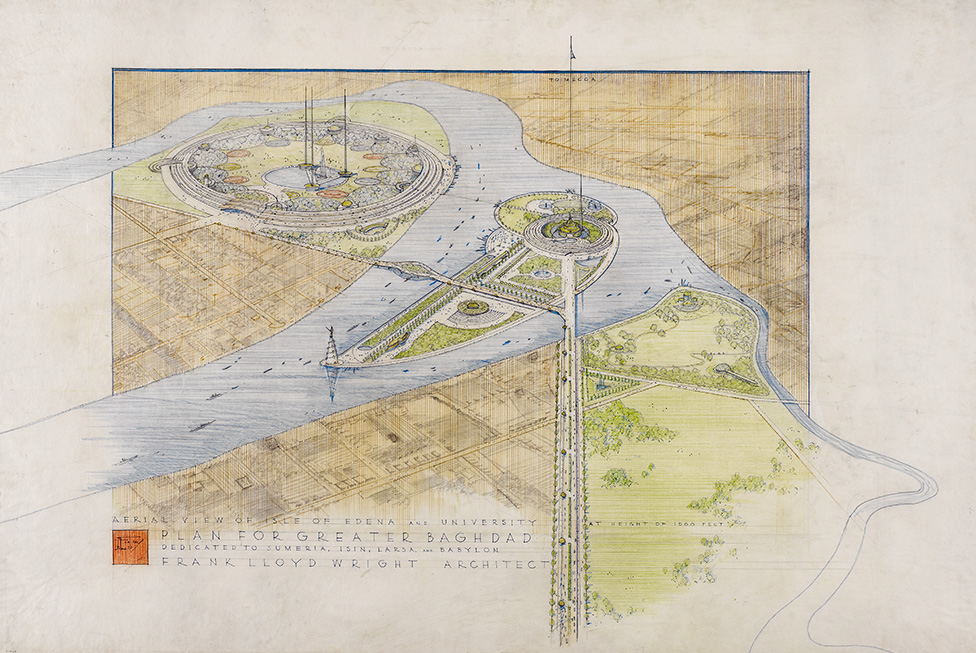

Wright, inspired by his encounters with ukiyo-e, moved distinctively away from the conventional standard of Beaux-Art style architectural drawings and developed a new drawing technique that was unique in its compositions, leaving large blank spaces on the paper and magnifying things in the foreground. Wright was said to have been building in his brain even before the actual building took shape, whose drawings sometimes reveal his thoughts more directly than the realized buildings. This exhibition presents you with a variety of beautiful drawings depicting his architectural masterpieces.

2.A century-old model of the Imperial Hotel on display as a 3D-printed replica using scanned data from the original

Wright sent the original model to Goichi Takeda, a professor at Kyoto Imperial University (current Kyoto University), on his return to the U.S. Takeda established a close relationship with Wright and contributed to his acceptance in Japan. The plaster of the original model had deteriorated in the course of one hundred years since it was created, which made it difficult to tour with the exhibition. The organizers requested Kyoto University, where Takeda belonged, to collaborate with Kyoto Institute of Technology (KIT) to reproduce the high-quality replica of the model using the 3D-printed technology of KYOTO Design Lab at KIT.

3.Experience Wright’s design in a life-sized model of a Usonian House

Wright started designing Usonian Houses in the late 1930s as low-cost, beautiful homes accessible to ordinary American citizens. Through the life-sized model based on the Baird House (Amherst, Massachusetts, 1940), an early example of wooden Usonian Houses, the visitors can experience the spaces leading from its entrance to the living area. This was realized with the cooperation of Mr. Ryosuke Isoya, who was an apprentice at Taliesin, Wright’s testing ground for his architectural education. The material used for the model is Japanese cedar from Izu, sawn by Mr. Isoya himself.