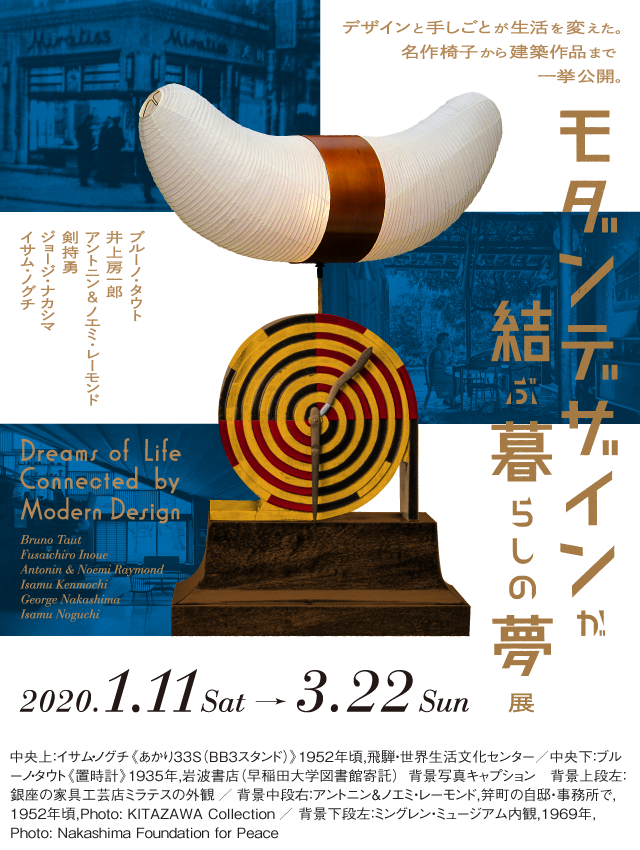

Dreams of Life Connected by Modern Design

General Information

- Dates

- Jan. 11– Mar. 22, 2020

【Notice: Extension of temporary closure】

Our temporary closing period will be extended until March 22 (Sun), as a measure against the further spreading of the coronavirus. And the “Dreams of Life Connected Modern Design” exhibition will be closed. We apologize for any inconvenience and we appreciate your understanding.

- Hours

- 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. (Admittance until 5:30 p.m.)

* Open until 8 p.m. (admittance until 7:30 p.m.) on Feb. 7 and Mar. 6

- Closed

- Wednesday

- Admission

- Adults: ¥800

Visitors aged 65 or over carrying proof of age: ¥700

Students (College): ¥600

Students (High / Middle school): ¥400

Admission is free for children in primary school and younger. Groups of 20 or more will receive a ¥100 discount per person (not including those aged 65 or over).

Admission is free for disability passbook holders and up to one accompanying adult.

- Organizers

- Panasonic Shiodome Museum of Art

- Support

- Embassy of the United States of America, Embassy of the Czech Republic in Tokyo, Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany, Goethe Institut Tokyo, Architectural Institute of Japan, Japanese Society for the Science of Design JSSD, Japan Industrial Designers’Association JIDA, Japan Interior Architects / Designers’Association, The Japan Institute of Architects, Minato City Board of Education

- Planning support

- Curators Inc.

- Exhibition design

- Naotake Maeda

Exhibition overview

In 1928, the Industrial Arts Institute was built in the northern Japanese city of Sendai, marking the establishment of Japan’s first national advisory for design. Five years later, the German architect Bruno Taut (1880 - 1938) was invited to join the institute as an advisor. There, he offered advice to Isamu Kenmochi (1888 - 1976) and his colleagues. That same year, the architect Antonin Raymond (1888 - 1976) and his wife, the interior designer Noémi Raymond (1889 - 1980), met the businessman Fusaichiro Inoue (1898 - 1993). Inoue was a patron of the arts scene in Takasaki, a city known for its traditional craft cultures. In 1934, Inoue invited Taut to visit Takasaki—an encounter that led to crafts designed by Taut being sold at a furniture shop called Miratiss. These exchanges symbolized a growing movement throughout Japan and worldwide of designers connecting to discuss how modern design could enrich lives in unprecedented ways.

Modern design was characterized by mass production—made possible by developments in industry and science—which allowed for a design philosophy prioritizing functional elegance over decorative beauty. While Japanese craft artists and manufacturers attempted to adapt this global trend to Japanese lifestyles and customs, architects and designers from around the world were simultaneously uncovering the modern aesthetic already residing in Japanese architecture and craftsmanship. It was the intertwining of these two trends that led to the birth of aesthetically stunning products that could not be defined purely by functionalism.

This exhibition introduces the works of Taut, Inoue, the Raymonds, and Kenmochi, as well as furniture designer George Nakashima (1905 - 1990) and sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904 - 1988), through 160 items including crafts, furniture, architectural designs, scale models, and photographs dating from the 1930s to the 1960s. Together, the items will convey how the designers developed their dreams of a better world following the Second World War, and how they communicated those hopes to the next generation.