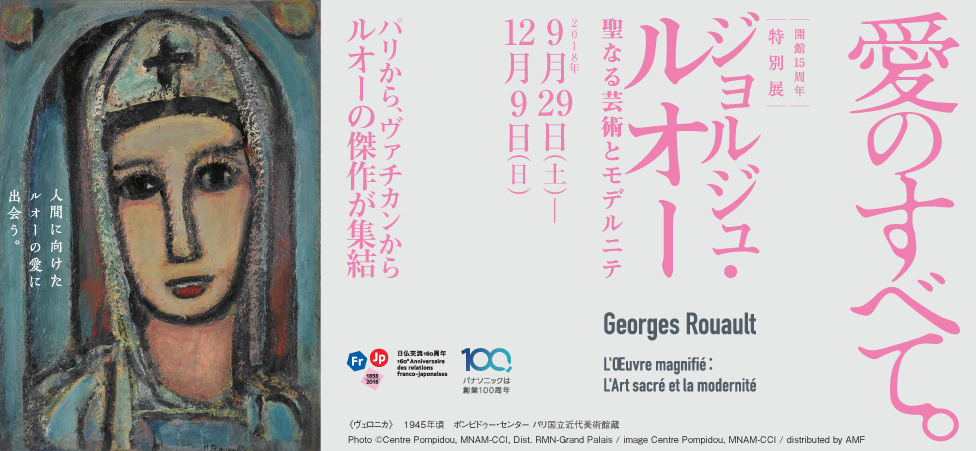

Georges Rouault L'Œuvre magnifié: L'Art sacré et la modernité

General Information

- Dates

- Dates:Sept. 29 – Dec. 9, 2018

- Hours

- 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. (Admittance until 5:30 p.m.)

* Oct. 26 and Nov. 16: 10 a.m. – 8 p.m.(Entry until 7:30 p.m.)

- Closed

- Wednesday (except Nov. 21 & 28 and Dec. 5)

- Admission

- Adults: ¥1,000

Students (College): ¥700

Students (High / Middle school): ¥500

Visitors aged 65 or over carrying proof of age: ¥900

Groups of 20 or more will receive a ¥100 discount per person (not including those aged 65 or over).

Admission is free for children in primary school and younger.

Admission is free for disability passbook holders and up to one accompanying adult.

- Organizers

- Panasonic Shiodome Museum, NHK, NHK Promotions, The Tokyo Shimbun

- Support

- Embassy of France in Tokyo / Institut français du Japon, Minato Ward Board of Education

- Participation

- Mitsumura Printing Co.

- Cooperation

- Japan Airlines

- Special Cooperation

- Fondation Georges Rouault

Exhibition overview

Sacred art plays a central role in the oeuvre of Georges Rouault (1871 -1958), one of the most important French artists of the 20th century. The exhibition will use these works to explore Rouault’s lifelong pursuit of depicting the immaculate beauty of love.

Rouault was a devout Christian who produced many works throughout his life that depicted religious motifs, such as the Cross and the Crucifixion. Through these motifs, he expressed the concepts of human suffering, grace, and forgiveness. These works of sacred art continue to captivate people from a wide range of cultural and geographic backgrounds. Although Rouault chose traditional subjects, the methods he employed in his art were revolutionary for their time. His themes, meanwhile, reflect a deep insight into the society and people of his era. It is this modernity that the exhibition will explore, through looking at the meanings behind his works of sacred art.

Consisting of 90 works—primarily oil paintings—the exhibition will represent a diverse overview of Rouault’s art. Highlights will include Automne ou Nazareth and other works which Vatican Museums, will lend out to Japan for the first time. In addition, many masterpieces from Rouault’s late period will make their way to the exhibition from Paris. Some of Rouault’s best-known depictions of Christ’s face and biblical landscapes from domestic and overseas collections will also be on display.