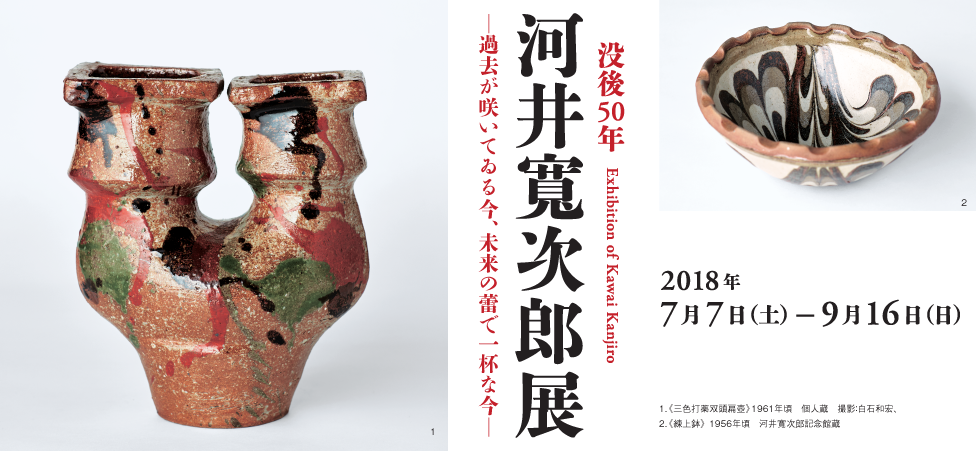

Exhibition of Kawai Kanjiro

General Information

- Dates

- July. 7 – September. 16, 2018

- Hours

- 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. (Admittance until 5:30 p.m.)

- Closed

- Wednesdays, August. 13 – 15

- Admission

- Adults: ¥1,000

Students (College): ¥700

Students (High / Middle school): ¥500

Visitors aged 65 or over carrying proof of age: ¥900

Groups of 20 or more will receive a ¥100 discount per person (not including those aged 65 or over).

Admission is free for children in primary school and younger.

Admission is free for disability passbook holders and up to one accompanying adult.

- Organizers

- Panasonic Shiodome Museum, The Mainichi Shimbun

- Support

- Minato Ward Board of Education

- Participation

- Daishinsha Inc.

Exhibition overview

Kawai Kanjiro was born in 1890 in Yasugi, Shimane Prefecture. He graduated from Matsue Middle School in 1910 and enrolled in the ceramic engineering program at the Tokyo Higher Polytechnic School (present-day Tokyo Institute of Technology). It was here that he met his lifelong friend, Hamada Shoji.

Kawai further developed his ceramics skills at the Kyoto Research Institute for Ceramics. In 1920, he inherited Kiyomizu Rokubei’s kiln shed on Gojozaka Street in Kyoto, and he converted it into a workshop and residence. Already branded a genius after his first solo exhibition, Kawai went on to craft numerous acclaimed works using techniques inspired by the intricate production processes found in ancient Chinese and Korean pottery. Despite his success, Kawai gradually lost interest in this style. In 1924, he was introduced to Yanagi Soetsu by his friend Hamada and, inspired by Yanagi, completely transformed his style; he began to craft works that were sturdier and more utilitarian. The three men went on to initiate the mingei folk arts movement and, in 1936, established the Japan Folk Crafts Museum; Kawai was appointed a board member. Following the Second World War, Kawai established a distinctive style characterized by bright, colorful glazes, a sense of heft, and decorative variety. Although he continued to focus on utilitarian designs, he never did so at the expense of his immense and uninhibited creativity. This is the reason why, fifty years after his death, Kawai continues to receive praise around the world for his work.

In addition to works from the collection of Kawai Kanjiro’s House—a museum converted from Kawai’s Kyoto home—this exhibition will display ceramic works from other collections, as well as woodcarvings, books, and furnishings. The ceramic works on loan from Yamaguchi University are particularly notable, as they have never before been publicly displayed in Japan. Together, the items will offer a comprehensive overview of Kawai’s work and provide insight into his deep spirituality. The exhibition will also feature a special display of Kawai’s works in the Panasonic Collection that were purchased by Panasonic founder Konosuke Matsushita. The display includes a Panapet R-8 transistor radio, which was launched around the time that Matsushita nominated Kawai for an Order of Culture award; Matsushita gifted Kawai with a Panapet R-8 to mark the occasion.